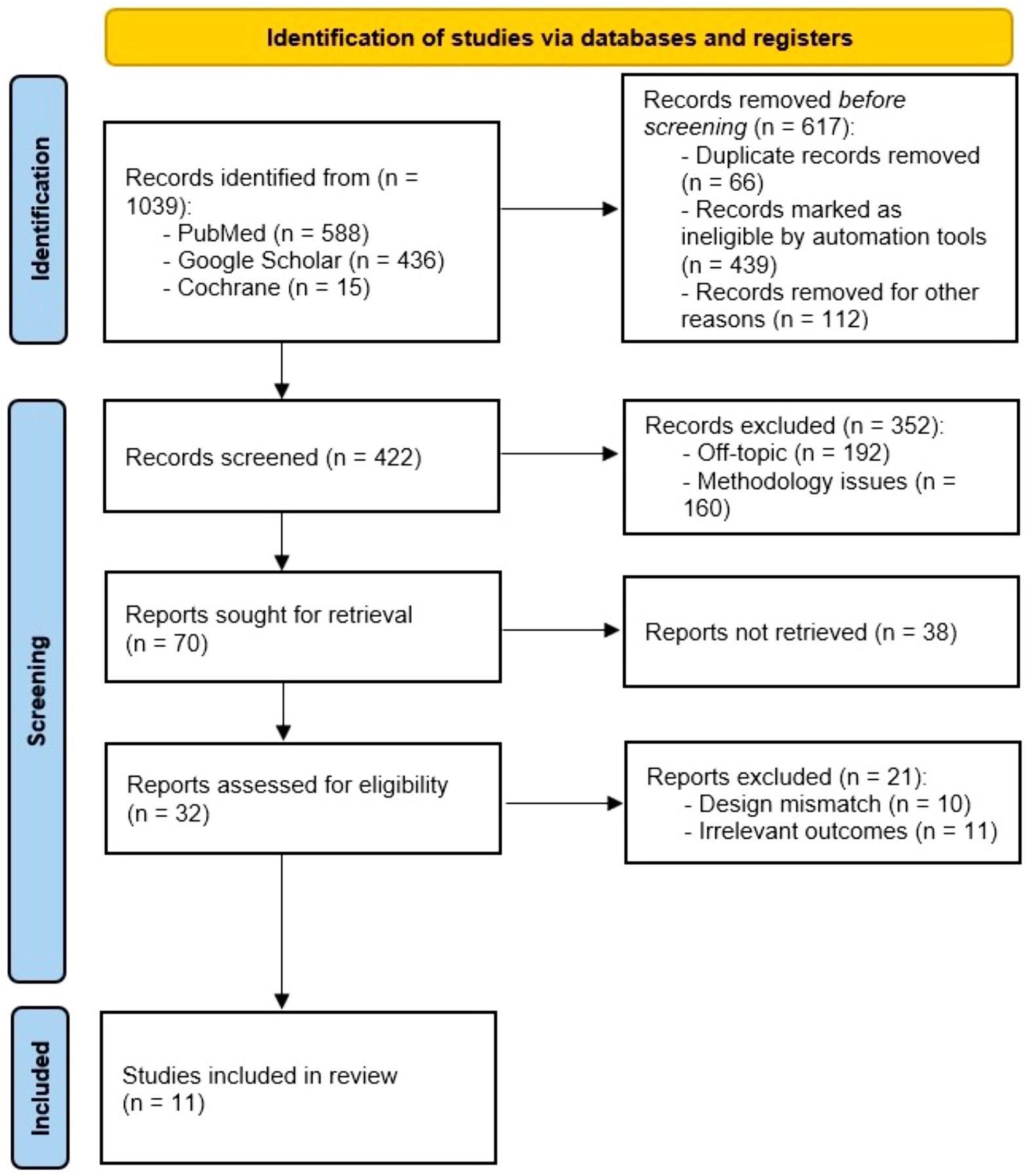

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart illustrating the study selection process.

| Cardiology Research, ISSN 1923-2829 print, 1923-2837 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, Cardiol Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.cardiologyres.org |

Original Article

Volume 15, Number 3, June 2024, pages 153-168

Comparative Efficacy of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Versus Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting in the Treatment of Ischemic Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Recent Randomized Controlled Trials

Figures

Tables

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; IHD: ischemic heart disease; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. | ||

| Language | English, Russian | All other languages |

| Publication timeframe | 2019 - 2024 | Older |

| Type of studies | Randomized controlled trials | Perspective, case study, reviews, grey literature |

| Region | All | No exclusion |

| Target population | Patients with IHD suffering from triple-vessel coronary artery disease and left main coronary artery occlusion | Patients with low SYNTAX scores |

| Context | Evaluation of the efficacy of cardiovascular interventions: PCI and CABG | Other surgical or non-surgical interventions |

| No. | Study | Location | Study design | Participants | Intervention | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CI: confidence interval; FFR: fractional flow reserve; GKR: gamma knife radiosurgery; HCR: hybrid coronary revascularization; HR: hazard ratio; MCCEs: major cardiac and cerebrovascular events; MV-PCI: multivessel percutaneous coronary intervention; RR: repeat revascularization; SPECT: single-photon emission computed tomography; SVG: saphenous vein graft; TOs: total occlusions. | ||||||

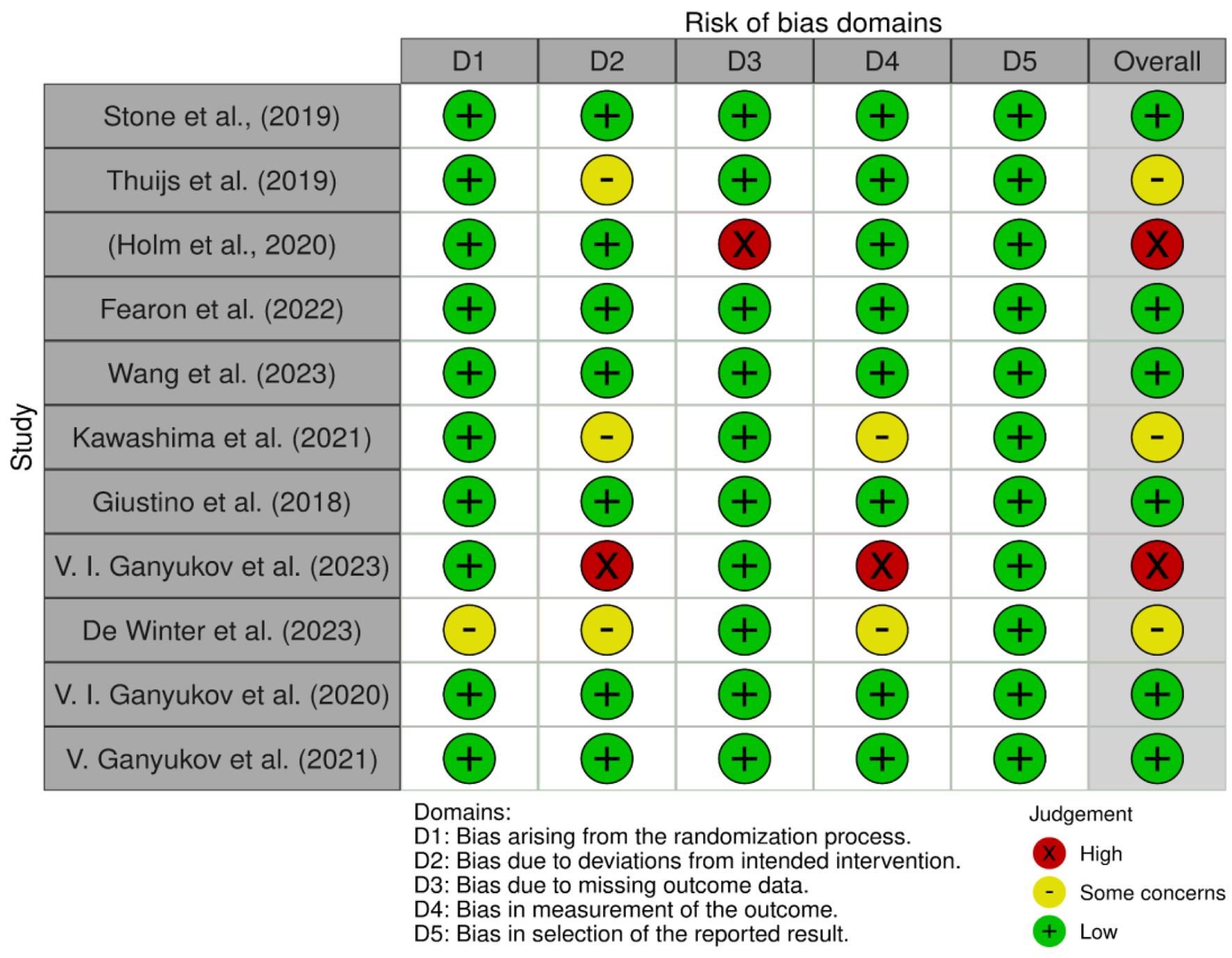

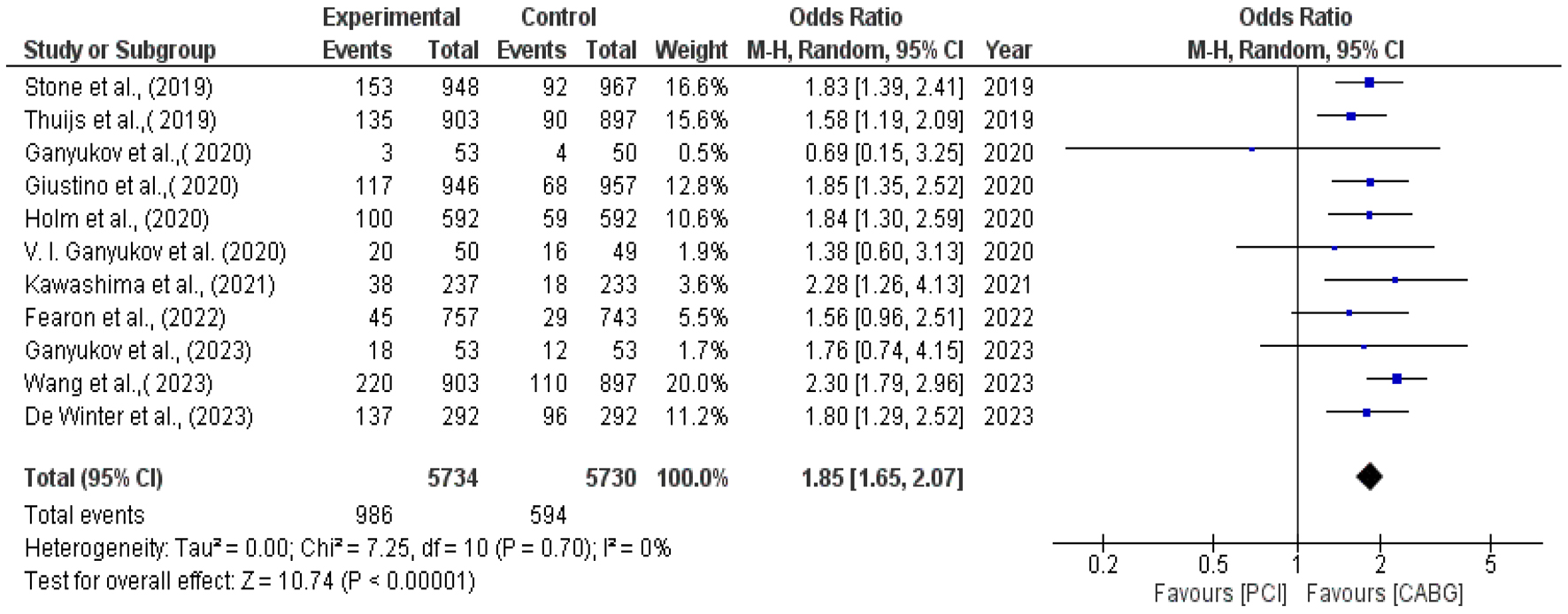

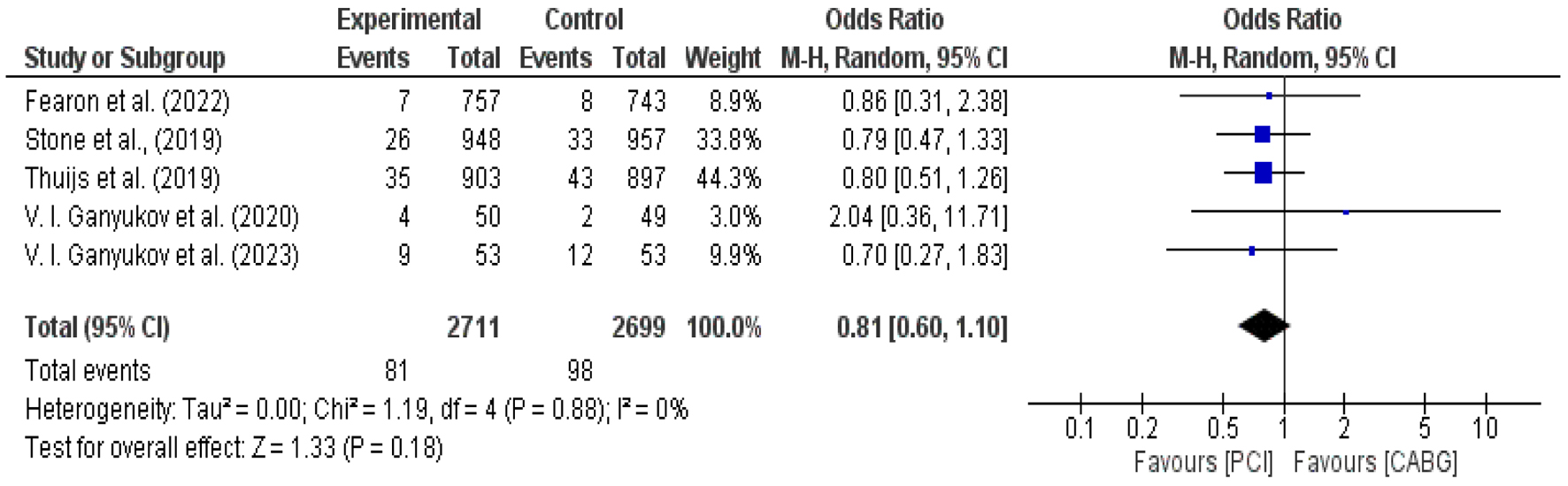

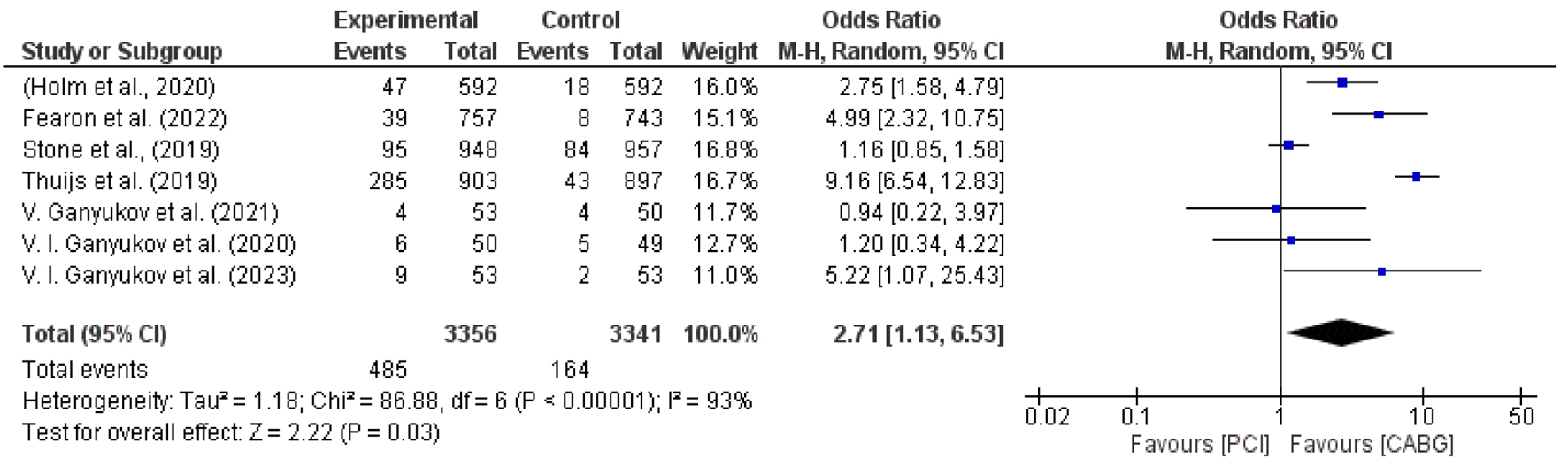

| 1 | Stone et al (2019) [22] | New England | Randomized controlled trial | A total of 1,905 patients with left main coronary artery disease were randomly assigned to PCI (948 patients) or CABG (957 patients). | The SYNTAX score was used as an eligibility parameter based on CAD for patients with a score of 32 or less. Patients were eligible to participate in the trial if they had greater than 70% stenosis of the left main coronary artery. | After PCI compared to CABG, ischemia-driven revascularization was more common (16.9% vs. 10.0%; difference, 6.9 percentage points; 95% CI: 3.7 - 10.0). Regarding the composite outcome of mortality, stroke, or myocardial infarction, there was no statistically significant difference observed between PCI and CABG in individuals with left main coronary artery disease. |

| 2 | Thuijs et al (2019) [23] | Germany | Randomized controlled trial | A total of 1,800 patients were randomly assigned to either the PCI (n = 903) or CABG (n = 897) group in a randomized controlled trial conducted in 85 hospitals across 18 North American and European countries. | Over 10 years, patients with de novo three-vessel disease and left main coronary artery disease were randomly assigned in a 1:1 fashion to either the PCI or CABG group. | At the 10-year follow-up, no significant difference in mortality rates was observed between PCI and CABG for patients with left main coronary artery disease. However, significantly lower mortality was found in cases of three-vessel coronary artery disease treated with CABG. Among patients with three-vessel disease, 28% had died after PCI compared to 21% after CABG (HR 1.41 (95% CI: 1.10 - 1.80)). For patients with left main coronary artery disease, 26% had died after PCI, versus 28% after CABG (HR 0.90 (95% CI: 0.68 - 1.20), P-interaction = 0.019). |

| 3 | Holm et al (2020) [24] | England | Randomized controlled trial | A total of 1,184 patients, with 592 patients in each group, were included in this analysis. | The NOBLE trial enrolled patients with left main coronary artery disease requiring revascularization and randomized them in a 1:1 ratio to receive either PCI or CABG. The trial was specifically designed to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of these two interventions over 5 years. | All-cause mortality was estimated at 9% after PCI versus 9% after CABG (HR 1.08 (95% CI: 0.74 - 1.59); P = 0.68); non-procedural myocardial infarction was estimated at 8% after PCI versus 3% after CABG (HR 2.99 (95% CI: 1.66 - 5.39); P = 0.0002); and RR was estimated at 17% after PCI versus 10% after CABG (HR 1.73 (95% CI: 1.25 - 2.40); P = 0.0009). |

| 4 | Fearon et al (2022) [25] | Belgium, Hungary, Netherlands | Randomized controllded trial | Of the 1,500 patients enrolled, 757 were randomly assigned to undergo PCI and 743 to undergo CABG at multiple centers. | Endpoints were investigated for 1 year. The major inclusion criterion was the presence of three-vessel coronary artery disease, defined as at least 50% diameter stenosis as assessed by visual estimation in each of the three major epicardial vessels. | The incidence of the composite primary endpoint (MCCEs) was 10.6% among patients randomly assigned to undergo FFR-guided PCI and 6.9% among those assigned to undergo CABG (HR 1.5; 95% CI: 1.1 to 2.2) (P = 0.35 for noninferiority). The incidence of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke was 7.3% in the FFR-guided PCI group and 5.2% in the CABG group (HR 1.4; 95% CI: 0.9 - 2.1). |

| 5 | Wang et al (2023) [26] | Netherlands, Germany | Randomized controlled trial | A total of 1,800 patients were enrolled, with 903 randomly assigned to PCI and 897 assigned to CABG. | Patients with triple-vessel coronary artery disease were included. | Among patients requiring RR, those who underwent PCI as initial revascularization had a higher risk of 10-year mortality compared to those who underwent initial CABG (33.5% vs. 17.6%, adjusted HR: 2.09, 95% CI 1.21 - 3.61, P = 0.008). RRs were recorded at 5 years. |

| 6 | Kawashima et al (2021) [27] | USA | Randomized controlled trial | Of the 1,500 patients enrolled, 757 were randomly assigned to undergo PCI and 743 to undergo CABG at multiple centers. | By the protocol design of the SYNTAX trial, patients with acute myocardial infarction were excluded, and patients with TOs were included under the inclusion criteria. | The status of TO revascularization among the treatment groups was as follows: in the PCI group, 29.9% vs. 29.4%; adjusted HR: 0.992; 95% CI: 0.474 - 2.075; P = 0.982; and in the CABG arm, 28.0% vs. 21.4%; adjusted HR: 0.656; 95% CI: 0.281 - 1.533; P = 0.330. |

| 7 | Giustino et al (2018) [28] | USA | Randomized controlled trial | A total of 1,905 patients were randomly assigned, with 948 to PCI and 957 to CABG. | All patients were required to have low or intermediate anatomic complexity of coronary artery disease, as defined by a site-determined SYNTAX score of 32 or less. At the time of the present analysis, all patients had completed 3 years of follow-up. | During the 3-year follow-up, there were 346 RR procedures among 185 patients. PCI was associated with higher rates of any RR (12.9% vs. 7.6%; HR: 1.73; 95% CI: 1.28 - 2.33; P = 0.0003). |

| 8 | Ganyukov et al (2023) [29] | Kemerovo | Randomized controlled trial | The study included 155 consecutive patients with multivessel coronary artery disease, of whom 53 underwent PCI and 53 underwent CABG. | The primary endpoint of the study was residual ischemia 12 months after revascularization, as determined by data from SPECT. | Statistically significant differences were observed between the CABG and PCI groups in the incidence of myocardial infarction (12.8% and 16.3%; P = 0.12), stroke (4.2% and 10.2%; P = 0.13), and RR (23.4% and 34.7%; P = 0.11). |

| 9 | De Winter et al (2023) [30] | Amsterdam, USA | Randomized controlled trial | A total of 584 participants will be randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either a strategy of native coronary artery PCI or SVG PCI, with 292 patients in each group. | Clinical indication for revascularization, as determined by the local Heart Team, was based on symptoms, documented ischemia, and viability. | A 3-year MACE rate of 47% was observed after bypass graft PCI, whereas the event rate for native vessel PCI in these patients was 33%. |

| 10 | Ganyukov et al (2020) [32] | Russia | Randomized controlled trial | A total of 155 consecutive patients were randomized to CABG (n = 50), HCR (n = 52), or MV-PCI (n = 53). | The mean age was 62 ± 7 years, and the majority of participants were men (71.6%). The mean follow-up duration was 52.5 months, with a minimum of 36 months. | The occurrence of the study endpoints at 3 years was available for 98% and 94.3% of the included patients for CABG and PCI, respectively. |

| 11 | Ganyukov et al (2021) [31] | Russia | Randomized controlled trial | A total of 155 patients with multivessel coronary artery disease were randomized into three groups: CABG (50 patients), HCR (52 patients), and MV-PCI (53 patients). | The primary endpoint was residual ischemia at 12 ± 1 months as determined by SPECT. Approximately one-half of the study patients had 2-vessel disease (50.3%), while the other half had ≥ 3 vessel CAD (49.7%). | Statistically significant differences in the incidence of myocardial infarction between the groups of CABG, GKR, and PCI (12.8%, 8.5%, and 16.3%; P = 0.12), stroke (4.2%, 6.4%, and 10.2%; P = 0.13), and RR according to clinical indications (23.4%, 23.4%, and 34.7%; P = 0.11) were also not observed. |

| No. | Study | No. of patients | Mean age (years) | Medical history | % Stenosis | Intervention | Stent thrombosis (no. of events) | Incomplete revascularization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LM-CAD: left main coronary artery disease; MV-CAD: multivessel coronary artery disease; 3VD: three-vessel disease; ACS: acute coronary syndrome. | ||||||||

| 1 | Stone et al (2019) [22] | 1,905 | 66.0 ± 9.6 | 80.5% of the patients had distal LM-CAD. | NR | Fluoropolymer-based cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stents | 16 | 153 |

| 2 | Thuijs et al (2019) [23] | 1,184 | > 21 | Patients with de novo 3VD and LM-CAD | NR | Paclitaxel-eluting stents | NR | NR |

| 3 | Holm et al (2020) [24] | 1,201 | 66.2 | Stable angina pectoris, unstable angina pectoris, or ACS; LM-CAD | > 50% | Umirolimus-eluting stents | 19 | 155 |

| 4 | Fearon et al (2022) [25] | 1,500 | < 65 or ≥ 65 | ACS | NR | Zotarolimus-eluting stents | 6 | 74 |

| 5 | Wang et al (2023) [26] | 1,800 | 64.6 ± 10.4 | 3VD and/or LM | NR | Paclitaxel-eluting stents | 5.0 ± 2.2 | 238 |

| 6 | Giustino et al (2018) [28] | 1,905 | NR | LM-CAD | ≥ 70% visually or 50% to < 70% via CA | Cobalt-chromium fluoropolymer-based everolimus-eluting stents | 8 | 346 |

| 7 | De Winter et al (2023) [30] | 584 | > 18 | Coronary artery lesion(s) and the SVG lesion(s) | > 50% | Everolimus-eluting stents | NR | NR |

| 8 | Ganyukov et al (2020) [32] | 155 | 62 ± 7 | Femoropopliteal lesions | NR | Paclitaxel-eluting stents | NR | NR |

| 9 | Ganyukov et al (2021) [31] | 155 | 62 ± 7 | MV-CAD | ≥ 70% | Everolimus-eluting stents | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 9 |